Fishing for rejections

The moment I realised I had to make my art & the data behind my arts funding failures and successes

Hello, I’m Stevie Mackenzie-Smith. I’ve just moved to Substack from Patreon. You can find a updated archive of new works here. I’m a writer of narrative non-fiction and memoir. I write newsletters about creativity, daily life, how we spend our time, work, pleasure, ambition and interdependence. In the words of Eileen Myles: “a career is just giving yourself prompts” – and so I also write about the ‘prompts’, or creative projects I’m undertaking as a way of figuring out: what are we supposed to do with ourselves here?? What does a good life look like?

In early 2023 I was very depressed and burnt out, and finally I saw that I simply could no longer continue scrabbling around for commercial copywriting work that ate my soul. It was the new year and I spent the low-light winter days working from home on shift for an agency, 9-6pm. What I remember most vividly about that time is all the crying at my desk.

There are only so many times you can dissolve at your desk, unable to comprehend how to write a seemingly easy piece of copy for a furniture empire. I wasn’t well. I made to decision to leave this freelance gig early; quitting brought huge relief in itself. I signed onto Employment and Support Allowance and I slept a lot. Sometimes I was exhausted from walking up the stairs. Days and weeks passed, I waited to see what different my new prescription of anti-depressants might make.

It was a low time for me, but there was also something powerful about surrendering. It reminded me of the early pandemic, when everything felt a numb. In March 2020 it was the restrictions that led the size and personal geography of a day to shrink. One stupid local walk, online quizzes. This time, in 2023, my world once again felt small, because resting became the only thing I needed to do. I dragged myself on slow walks with podcasts. I accepted my dazed state. All I wanted was to listen to what other people had to say about mental health, the purpose of life and work, and how we spend our days. Because I badly wanted to find an answer for myself.

I was a decade into working jobs I either didn’t like, or which couldn’t possibly bring in the money to sustain a living. I couldn’t see that I had any agency over this situation. Sure, copywriting for big brands wasn’t what I wan’t to do, but it wasn’t like I was selling arms! Plus, I could command a day rate of £350, which was clearly insanely and unreasonably great. I believed I was being overly sensitive, and that I was actually very lucky. I told myself I should find a way to make peace with this situation in order to live. I should find a way to wear it all more lightly.

The thing about having this time off sick in 2023 is that I began to realise that I couldn’t wear it more lightly, and that was okay. I could wish and wish to be the kind of person who could turn up, work and clock out again. The kind of person able to do this without feeling spiritually and existentially dead. But I just wasn’t that person. Trying harder wouldn’t turn me into that person. My breakthrough moment came when I saw that trying to contort myself into work situations that simply didn’t work for me was killing me, not figuratively, but literally. It was dimming everything natural, authentic and sparkling in me. I was allowed to understand that reality, and listen to it. In fact, I didn’t have a choice but to listen. Look at what ignoring it had done for me.

I think in these kinds of moments, of reaching a very low place, you become so sick of yourself. I became so utterly sick of myself that the only solution I had left was to stop standing in my own way. I was so sick of all the terrible things I told myself. The awful internal monologue. I had to drop my own cruel judgement of myself. So, I started trying to let myself do things without shaming or embarrassing myself. For one, I listened to Alistair Campbell’s book about depression on audiobook without worrying that this made me a Centrist Dad. I listened to every single podcast I could find featuring Rick Rubin during the release of his book on the creative process. I enjoyed these things! It was exactly what the moment called for. Listening to Rubin helped me return to what I already knew, in a deep place, but had lost touch with. Looping the streets in Norwich, I heard him talk about ‘creative source’ and I started to feel that I was waking up. It was like seeing the night sky, or hearing previously muted birdsong, with a sharpened clarity. Natural intuitions returning.

All this to say, and I’m skipping plenty, that in 2023 I started to put myself out there again. Baby steps. Between my meagre ESA payments and some savings, I remained not working for a few more weeks. My husband did the food shopping, the cooking and washing up – he handled household tasks I was too exhausted for. I listened to podcasts with artists describing the material conditions under which they made work, and how they make it work (if at all). This led me to get curious about arts funding and writing residencies, and after that, I learned the special language of writing funding applications. I learned that I could call myself an artist. Even as a writer. I could apply for arts funding. Even as a writer. The only person that would anoint me, was me.

I was already familiar with the concept of aiming for 100 rejections in a year as a successful measure of progress. That by putting yourself out there, it was a statistical inevitably that you’d have successes also. This was a concept that gained a lot of traction in journalism and writer Twitter communities in the late 2010s. And honestly, I’d found the concept disingenuous. I didn’t see that rejections could be anything other than awful and soul-sapping – why not be honest and admit that you’re collecting rejections only in service of your genuine desire: eventual acceptance.

But that spring I ate up Katie Hale’s blog posts about rejection. Hale shared, in delicious detail, data from across her year. As a writer she’d applied to prizes, residencies, competitions, magazines submissions, retreats, funding, and more; she recorded this information transparently in pleasing pie charts. A pattern started to emerge. A success rate of about 17%. This included straightforward ‘successes’, like receiving funding, or making the longlist of a prize.

Something about Hale dissecting her ‘failures’ and ‘successes’ in this way, for all to see, was actually buoying. At that moment in time I wasn’t applying to anything like this. I felt guilty because I thought I should – but I wasn’t. Being successful in literally anything would be an improvement on where I was at that point. Which was a place of stagnation; I had hundreds of pages of writing, some of it great, much of it bad; but I had no place to channel that into forward motion. I was too scared to share my work with anyone because I knew it wasn’t ready. I needed something to get me to that next stage. Putting myself out there could be my marker of ‘success’, a word that still makes me feel a bit gross.

Katie Hale’s tasty pie chart, from her 2022 rejection round-up.

I got advice on how to put together a writer bio and an artist statement; elements that form the bones of any application. I was able to write about the podcast I’d made years ago, and the fact that my blog had been well-read and featured in the press back in the day. But otherwise I was sparse on recent detail or otherwise ‘impressive’ writing credentials. Then, a discovered that might be another way. “You can also lie,” Gabrielle De La Puente writes of the time she created a fake exhibition for the sake of her CV:

“Collectively, between myself, the artists, the gallery space and even an online publication that lists upcoming shows, we told the lie of the exhibition together. I made the show ‘by appointment only’ and then ignored all the emails from people asking to visit. I had already gotten what I wanted in the photos, we all had.” - Gabrielle De La Puente, How To Get An Exhibition.

After reading this, I decided that I too would host a fake exhibition, of sorts. I printed my work and blue tac-ed it on the walls of my house. I set a listening station at my desk, with laptop and headphones sharing some of my audio works. My friend Sarah took photographs, so it was real. I invited friends. We ate moussaka. I added it to my CV.

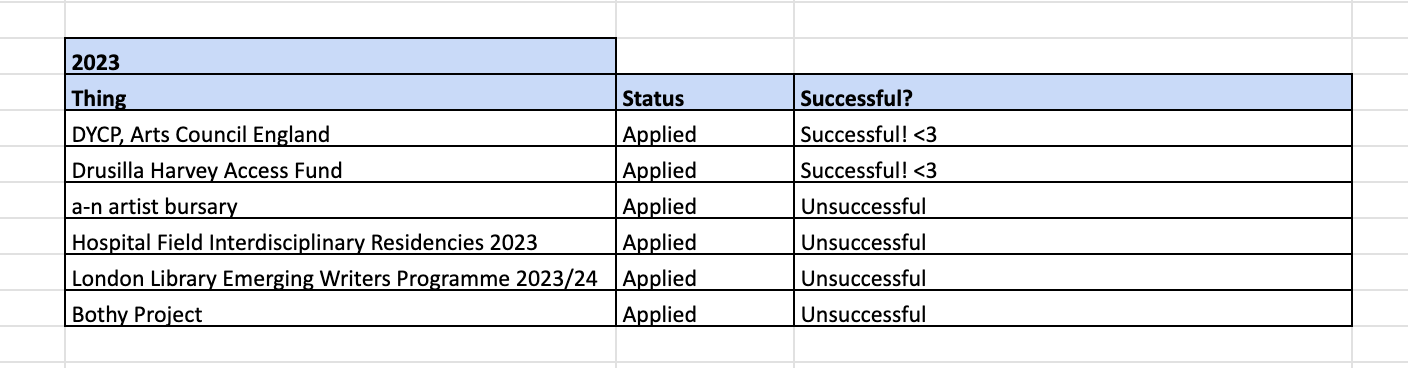

Later that year, I started to apply for opportunities I found either by searching online or finding them on Instagram. With a renewed zeal, I made a spreadsheet, and called it 'Fishing For Rejections’.

In 2023, I applied to:

-3 funding opportunities

-2 art residencies

-1 writers development programme

Of those, I got four rejections, and two were successful. A success rate of 33.3%! Or, if want to define success as simply applying in the first place… a rate of 100%.

I was ecstatic because of all the opportunities I applied for, the DYCP funding was the one I wanted the most. I knew it would make the most material difference, and buy me more time to stay in my mode of experimentation, while I figured out what working was going to look like for me. How I might go about making a greater chunk of my income from creative work. If that was even possible. I’d badly wanted to go onto the Hospitalfield residency, and onto the London Library programme, but getting the DYCP was more than enough for me. It felt like magic.

Even though writing these applications took up a great deal of time, thought and energy – the DYCP took about 4 months, from thinking to submission – it was personally worth me doing at that moment. Each application I completed gave me more content to repurpose for the next one. In theory, I could get them written a bit quicker each time. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that each application made me more likely to apply for something else. With each success, even the tiny ones (the Drusilla Harvey Access Fund, for example, gave me £70 towards a DIY writing retreat – hardly worth applying for), I had a new ‘credential’ I could add to my next application. Funders find credentials, or evidence that other organisations have already bet on you, reassuring. This isn’t right, or fair, and its not conducive to bringing more people into their true creative calling, which is something I want for everyone. But it’s what happens, and I have included ‘Recipient of Drusilla Harvey Access Fund’ on my applications since, even if the grant was an absolute (though much appreciated) pittance.

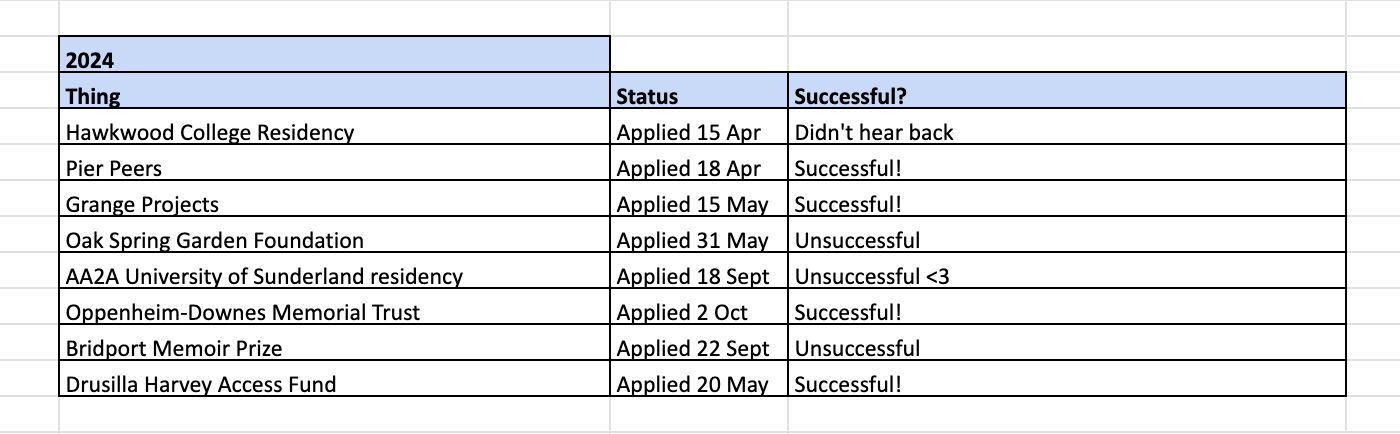

Here’s how 2024 panned out:

I have lots more to say about all of this, but I’ll leave it here for now. In the meantime here’s a post about what led to my successful Arts Council England DYCP application.

Please feel free to ask any questions about any of the above in the comments! As you’ll know if you’ve read this far, transparency and resource-sharing is what helped me to apply for all these opportunities in the first place. Hope this helps you to get the ball rolling in some way, please keep me posted if it does.

Ah this is such a great post, and so timely for me. This level of transparency is a godsend, because so often you're just flailing around on Instagram wondering if everyone is getting residencies and publishing deals and they all have private wealth or something. Loved every word. Tempted to revisit the DYCP now!!

Thank you for sharing! I burnt out twice before leaving and have been freelancing / experimenting now for 12 months. Last year I also successfully applied for some arts funding and was able to go to a week-long event in Berlin that I’d been wanting to go to for years. It was thrilling! I found out this week I didn’t get a commission I was hoping for and you’ve inspired me now to ‘go fishing’ for some funding opportunities / rejections (and most importantly keep a spreadsheet tally!)